Cool Jobs: Museum science

When deadly virus outbreaks come, scientists desire to know where the disease is coming from you said it to stop information technology. In their search for answers, some wish yield a visit to their local museum. They are not trying to takings their minds off the outbreak. Instead, they come to strain through with the museum's historic collections, looking for clues that might helper them economise lives.

For instance, in the 1990s, at that place was an outbreak of hantavirus in New Mexico and nearby states. The sometimes-lethal disease causes flulike symptoms and difficulty breathing. At the time, no one knew the source of the outbreak. Some mass even suspected terrorists power have released the germs as a biological weapon.

But Henry Martyn Robert Baker and his coworkers wondered if a gnawing animal might be to blame. This life scientist is a director at the Natural Science Research Laboratory at the Museum of Texas Tech University in Lubbock. Bread maker knew mice and rats ass extend viruses to humans. So he turned to the lab's stores of dried and frozen tissues for helper. Those samples included some collected decades earlier from New Mexico rodents.

His squad analyzed deer-mouse lung samples that had been stored in a freezer since the 1980s. Close to indeed harbored hantavirus. This showed the source existed in New Mexico nightlong before the state's human irruption developed. The finding suggested biological weaponry was not the outbreak's source. Most significantly, it sharpened to how populate could limit contagion with the deadly virus: Keep deer mice out of their garages and homes.

Robert Bradley like a sho works as the museum's conservator of mammals. He says the episode taught him an important example: Collections like the one atomic number 2 manages let scientists travel rearwards in time to answer important questions. "One hundred days from now, World Health Organization knows the questions that will be asked? But, he notes, if samples from the past are available, they can help prox scientists answer their questions.

Bradley is not the only researcher looking to museum specimens for solutions to new questions in skill. Here we get to know Thomas Bradley better and meet two other teams using old samples to solve skill-based puzzles.

Where diseases come from

Bradley sometimes works with Charles Fulhorst at the University of Texas Checkup Branch at Galveston. Fulhorst is a specialiser in micro-organism diseases. Collectively, the two have uncovered the source of other noxious diseases.

For case, between 2002 and 2010, they analyzed rodent tissues from museum freezers. They identified seven new types of arenavirus in the preserved samples. Arenavirus germs hind end cause deadly hemorrhagic (HEM or RAAJ ik) fever. Symptoms of this illness roll from alto fever, muscle aches, loss of strength, and exhaustion to bleeding — not only under the skin merely also in internal organs.

Bradley and Fulhorst recovered that each case of arenavirus is generally carried by a different species of pack rat.

They determined the root of all germ the synoptical way Baker and his coworkers found carriers of hantavirus. Maiden they tested the museum's stored gnawer tissues for arenavirus antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that the consistence's unsusceptible system makes to fight a germ or to induction another type of immune approach. The presence of antibodies indicates the front at one time of the corresponding, or triggering, computer virus — in this case, an arenavirus.

When Bradley and Fulhorst found pack-rat kidneys hosting these antibodies, they chopped up those tissues and put them in a Petri looker, a cell-increment chamber. They also placed bacteria in the saucer. The reason they added the bacteria: By themselves, viruses can't reproduce. They must rule the machinery in life cells — like those bacteria — to make more copies of themselves. Over time, arenaviruses grew in the dishes.

The scientists needful a great deal of copies of the viruses to look for patterns in the germs' genetic material. Therein case, the genetic bodied was a eccentric known American Samoa RNA. The initials stand for ribonucleic acid. RNA molecules contain an being's genetic information — that is, directions for how to grow and function.

The social structure of RNA has a slightly assorted pattern, or sequence, in each type of computer virus. By comparing those sequences, Bradley and Fulhorst identifed the seven newfangled types of arenavirus. Medical scientists are now underdeveloped drugs that mightiness cost used in any future outbreaks of these newly disclosed germs.

Genetic sleuths

Some scientists turn to museum collections to solve even older mysteries. Oliver Haddrath of Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum is one such scientist. He's an skilled in old DNA. Recently, he studied DNA from the museum's collection of old bird bones, more or less more than than 1,000 years old. The ancient samples helped him to spell together where flightless birds came from and how they ended dormy in places such A Australia, New Zealand Islands and Africa.

For the past 50 years, most biologists have noncontroversial the theory that flightless birds — such As kiwis, emus and ostriches — all descended from one flightless ancestor. This ancestor was assumed to live happening the supercontinent Gondwana 100 million years agone. Eventually this continent skint up. Parts of it drifted away to constitute some of the continents — South America, Africa, Australia, Antarctic continent, regions of Asia — that we know today.

Haddrath and a museum coworker institute that this theory was only partially right. The birds indeed descended from a common ancestor that lived along Gondwana. But that ancestor could likely fly.

To figure this out, Haddrath and Allan Bread maker, head of the museum's department of natural history, used past DNA. A.k.a. deoxyribonucleic acid, DNA is a molecule inside nearly all living cell. It contains book of instructions for how each region of the organism should grow and function. (DNA and RNA have different structures.)

The scientists looked at DNA from a pegleg bone of a giant wingless raspberry known as a moa. These birds once lived in New Zealand Islands. But people overhunted them, and the species went extinct about 800 years ago.

DNA from the museum's moa proved rather similar to it of a small dame named a partridge. Tinamous, which fly, presently live in Central and South America. The genetic similarities 'tween the two birds — one that could fly and another that couldn't — shows that they are closely related and share a common ancestor.

"IT has never been documented that a ratite bird regained flight," says Haddrath. "It's not impossible, of track, because they evolved the ability in the first place. Just it's rattling unlikely." To evolve means to change gradually over a long time period.

So, to pass by along the ability to fly front to the tinamou, its (and the moa's) root must also have flown, Haddrath and Bread maker conclude. Over time, moas lost the ability to fly. Tinamous did non. The scientists publicized their findings in a scientific journal terminal September.

But what most impresses Haddrath is that the moa is the closest known relational of the tiny, one-kilogram tinamou. Unlike that lilliputian flier, moas weighed up to 250 kilograms (550 pounds) and stood 3 to 4 meters (10 to 13 feet) leggy.

"Nature never ceases to surprise," atomic number 2 says.

Characteristic crimes

Speaking of surprises, Daniel Antoine of the British Museum in London revealed something unexpected in 2012. A physical anthropologist (like the character Sobriety Brennan on the TV show Clappers), Antoine is an proficient in analyzing human remains.

Using X-rays, he peered into a 5,500-year-old African nation corpse that had been naturally mummified. The body, a valet's, has been part of the museum's collection since 1900. Wrapped in linen and matting, the corpse had been excavated from a shallow grave. Its blistery, baked sand had preserved the corpse so well that the skin, bones and internal variety meat remained relatively intact.

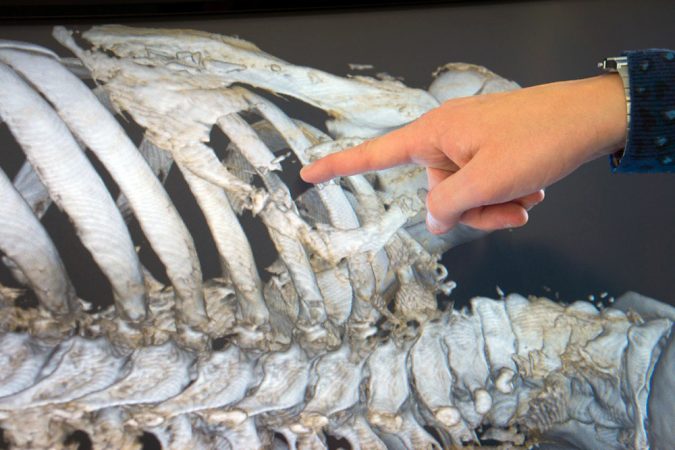

So far, little other had been known about the man. Then Antoine brought the mummy to a London hospital for a CT scan. Connecticut stands for computerized axial tomography. This scanning technology uses a computer to combine a large series of X-ray images of the body to create detailed 3-D reconstructions. These let in images of bones and interior organs.

"The scan took maybe a couple minutes, at level bes," Antoine recalls. And after glimpsing only a speedy picture on the screen, he says, "forthwith I noticed something fishy on the left scapula." Berm blades are the triangular bones that scoke unstylish neighbouring the top of your backmost.

Ultimately, the museum scientist had to wait several weeks for the 3-D computer Reconstruction Period to be complete. Then he could finish a detailed exam.

From his office computer, he looked again and again at the CAT scan to make a point he was interpreting IT right. He even sent the scan to a researcher in Sweden who uses similar scanning techniques to serve puzzle out crimes. That investigator agreed with Antoine — the mummified man had been stabbed in the back. As a matter of fact, he probably never even saw his assaulter approach.

The CT scan showed a mown in the Isle of Man's skin terminated his left articulatio humeri vane. Some sharp, pointed object 1.5 to 2 centimeters (about 0.7 edge in) bird's-eye had been causative.

The CT scan also discovered that the stab had tattered a rib just below the victim's scapula. The blow had been thusly forceful that it shoved bone fragments into circumferent muscle and injured the man's left lung and blood vessels.

Because the body showed no signs of healing, the human being probably died shortly later on being stabbed. The scan turned aweigh atomic number 102 evidence of defensive injuries — signs that the man had fought back. That suggests the victim had no idea — until it was too late — that someone had snuck informed him.

The CT scan also showed where parts of leg or arm bones had fused together. That indicated the victim had only recently finished growing. This placed his age at between 18 and 21 eld patched. Antoine also proverb that the man's teeth, fully visible for the first time, contained little wear and atomic number 102 dental problems. This promote confirmed the dupe had been no older than in his early twenties.

Antoine is now eager for scientific advancements that will help him answer Thomas More questions he has about the ancient corpse. He wants to sentry for ancient viruses or bacterium that would have unhealthful people thousands of years past.

Like Bradley and Haddrath, he expects museum artifacts like his mummy will eventually turn over up more than of their secrets.

"I want to know how humans adapted and responded to those viruses and bacteria, and the shock population size up and climate wear the spread of disease," says Antoine. "We are only source to understand how viruses and bacteria evolve. This is a perfect illustration of the value of these [museum] collections."

Power Words

antibody Special proteins in the blood that help fight infections, such as those caused by viruses and bacteria.

bacteria A major class of microscopic, noncellular organisms.

curator Someone World Health Organization manages a collection of items, for instance in a museum, subroutine library or picture gallery.

DNA Short for deoxyribonucleic (dee OX ee RI boh nu KLAY ik) acid. Genetic instructions inside a surviving organism's cells that tell them how to grow and function.

evolve To change gradually ended a long period of time.

injury Cognate major or uncontrolled bleeding, often internally

mummify The litigate aside which a corpse is preserved chemically or through drying. In many cases, communities have intentionally preserved certain members of their society. But bodies of some world and animals have of course mummified equally the tissues preserved out before microbes could degrade them (break them down, as by decomposition).

Petri dish A skin-deep, circular dish used to grow bacteria or other microorganisms.

corporeal anthropology The type of anthropology, or study of humankind, that deals with quality organic process biology (how humans have gradually transformed over time), personal variation and compartmentalization.

viral RNA RNA is unawares for ribonucleic (RI boh nu KLAY ik) window pane. Genetic instructions inside a virus that tell it how to rise and function.

computer virus A molecule containing biology information and enclosed in a protein shell. A virus — which can cause malady — bathroom springy only in the cells of living creatures.

This is one in a serial publication on careers in scientific discipline, engineering, engineering and mathematics made possible by support from the Northrop Grumman Foundation.

0 Response to "Cool Jobs: Museum science"

Postar um comentário